Kizzie, 2008

printed 2010

Kizzie, blind from the age of 16 loves being photographed, and when I call and arrange a visit she is always dressed and ready, her sister Martha assists her. I never tell her what to wear or how to pose, sometimes I indicate where she should stand and Martha helps position her or poses with her. She likes to wear glasses and a watch, as she did before her blindness occurred. Listening to my voice, she often decides how to pose. She is an ideal model. Martha describes to Kizzie in detail each Polaroid as we make them and we move, build and create an image together.

Martha and Kizzie in Mirror, 2005

Printed 2008

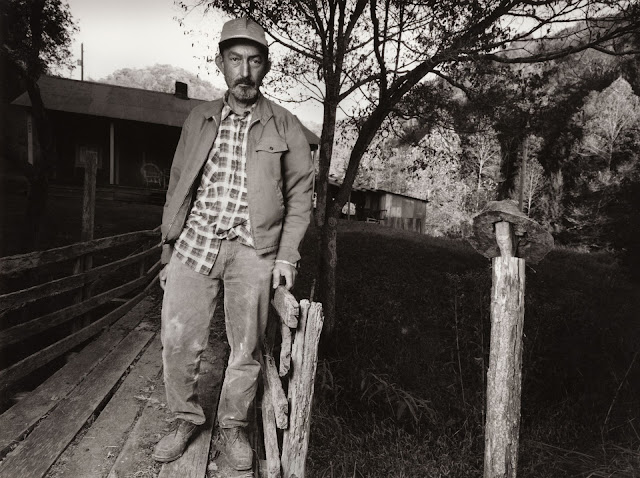

Merle, 1985

unpublished

Hindman

"But still, there is something which isn't yet clear—which I can't get with. Although there is real and warm love within families—there is something extremely opposite that—which manifest itself in feuds, shootings, cuttings, etc."

—John Cohen

Capturing The South

John and Teresa, 2008

unpublished

Eagle's Nest

Angie, 1992

unpublished

Leatherwood

Teresa and Family, 03

As published in Salt & Truth

Teresa and her 3 sons had lost their father in the Afghanistan War. When I asked to make a family portrait, to my surprise the boys ran for a stuffed raccoon from the mantel and began to argue about who should hold it, as it held their fathers dog tags. To them the raccoon immortalized the last image of the boy's father. After making several Polaroids in varied ways we exposed the film below with the 4x5 camera. The bottom left image is the one I selected to print.

4x5 contact sheets

Will post original 4x5 Polaroids when they are found.

Linda, Girl with Big Eyes, 1982

Linda, 2007

“Shelby Lee Adams’s subjects peer at the camera with an immodest curiosity. The viewers peer back, creating a circular scrutiny, an unsettling intensity—an education, as we turn page after page [scroll] of portraits which evoke fear, anger, compassion, empathy, and finally, a deeper connection to the brotherhood of Man.”

Quote from Appalachian Portraits endorsement, photographers first book published 1993.

—Robert Coles

Author Children of Crisis series

_______________________________________________________________________

Jacobs

Rosa Lee and Junior, 1986

The Jacobs Boys, 1984

Paul and Jerry, 1985

Paul with Mother and Bucket, 1985

unpublished

Shauna Faye and Stephanie Lynn, 2001

“Most mountain people, among ourselves are just open and loving to each other, we expect everyone to see us as we do—more caring, but some never here before, misunderstand, label and see us all unfairly.”

—Rachel Riddle, Leatherwood, Kentucky

Coalminer, 1988

published in Appalachian Portraits, 1993

Coal Pile, 2005

The Porch [Photo made in North Georgia], 1993

untitled [Photo made in East Texas], 1995

Haywood, 2000

Bobby, 2003

unpublished

"That's all any story is, you catch this fluidity which is human life and you focus a light on it and you stop it long enough for people to be able to see it.

—William Faulkner

Arnold, 93

______________________________________________

The Slone's

Leddie, 1983

Lonnie and Leddie [Sisters], 1985

Dan

Dan, Krissy and Leddie, 1993

Dan ad Flossie [inside], 99

Dan and Flossie [outside], 99

Dan and Flossie, 01

Dan Driving Straight To Hell, 98

Dan, 2005

Printed 2022

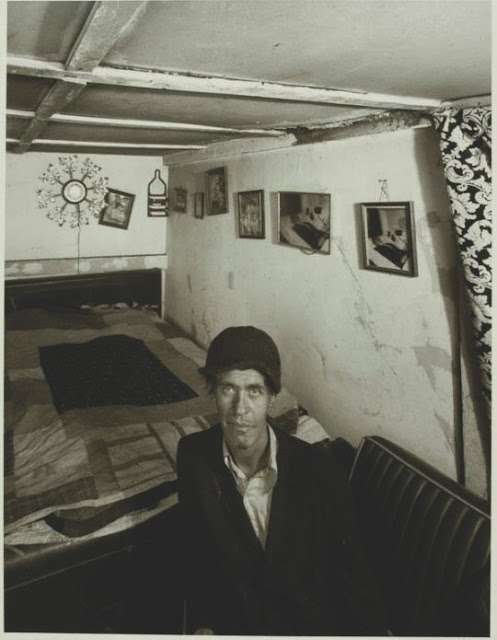

Bert, 1989

Bert Siting in front of Bed, 88

Bert with Guitar, 92

Bert Holding Home-Made Musical Harp, 1987

Bert with Jesus Pictures, 92

Lonnie and Bert, 1990

Leddie, Lonnie and Bert, 1988

Lonnie, 1985

Leddie, 1986

"Leddie with Children," 1990, Published in 1993 cover image for first book.

Wanda Lee and Stacy [Dan's daughter and granddaughter], 1985

Pete and Stacy, 99 [Rough Scan] Polaroid.

The Old Home Place, 1997

[Slone's old home, now gone, where we made many photographs.]

I coat and give some 4x5 Polaroids to everyone. I have not photographed Roland Johnson [man center on porch] before and do not expect to see him again. I ask him if he will sign a model release for me so that I could use this picture in one of my books. I always hate this part of my work, but Roland surprises me. He slaps his knees and says, " I was hopin' you'd get a picture of me for one of your books. I know all about you. I studied your pictures in the pen. You're like Danny Lyons, Bruce Davidson, and all them guys. I studied photography when I was in the La Grange State Penitentiary, and I know a lot about your pictures. "He continues, "What you are doing is expressin' yourself and showin' how you feel about us. Not everybody can do that! You'd do what you're doin' even if it cost you money, because you're interested in doin' what you love. You can see that in your pictures. Yeah, let me sign one of them model releases, I'd love to be in one of your books." I am somewhat taken back by this response and would later try to reproduce it as accurately as possible. I was not to meet Ronald again; Wanda Lee would later tell me that he was back in prison for breaking parole.

Published in Appalachian Lives, 2003, University of Mississippi Press.

Leddie, 2002

[Our last photo.]

__________________________________________________

Is it not one’s socio-economic-political status in life that grants one’s visibility as something more important or less significant? In portraiture and human representation, faced with the inconsistency or incompleteness of a person’s form, some feel entitled to say dispassionately, that face is unsightly and unimportant, especially those who look poor. If given a chance, cannot any form of humanity be elevated, redeemed and transformed by a faithful artistic portrayal?

—Shelby Lee Adams

Belinda and Martha, 2007

Vedessa and Robert, 2005

Ted and Friend, 2004

"Any but the most casual of viewers will be drawn into relationship with Adams' friends. Their eyes reveal that, unlike ordinary portraits, these "subjects" are looking through the window of the camera into our own faces, plumbing our depths, searching our cores to know what we are really like. And who, indeed, are we? Perhaps they know more than we."

"A book to be lived with, not merely scanned, Appalachian Portraits is both art and documentary. It is an unforgettable book, as Harvard's Robert Coles says, of "unsettling intensity."

—John B. Stephenson, president of Berea College

Lexington Herald-Leader, December 12, 1993

Reece and Martha Cole, 1999

Minerva and Jimmy, 1991

Prayer Before River Baptism

The New Bicycle, 2004

Polly, 1997

“You don’t make a photograph just with a camera. You bring to the act of photography all the pictures you have seen, the books you have read, the music you have heard, the people you have loved.”

—Ansel Adams

Dan and Jip, 1991 [father and son]

Dan and Jip, 2012

Granny with Jesus, 1992

Hooterville

Leonard's Back Porch, 1992

Brenda in Pistol City, 1983

Aunt Glade, 1975

Johnson's Fork

Travis, 2004

David, Bad To The Bones, 1985

Bobby, 1982

Pistol City

Dressed Up Stove Pipe, 1994

Photoworkshop 1995, Groningen, The Netherlands

Environmental Portraiture

_________________________________

"Just name a thing you want...I'll bring you a pretty."

—James Still

Pattern Of A Man & Other Stories*

Tools, 1994

Sight

Singularly, sight alone can be taken for granted, it often bounds our feelings and restricts our relationships to those so like ourselves, because we don't always want to work exploring our diverse cultures and peoples, remaining in our comfort zone.

The experience of an affirmative touch, a reassuring look, one's scent, a supporting hug all creates positive bonding—developing relationships, no matter what one's appearance, color or clan.

Acceptance begins with sight, then touch and an expanding heart together, all unifies us, making whole.

Yet, many resist when they see arduous differences. I have experience overcoming fears of the different, learning to keep myself flexible in the presence of others diverse. It takes practice sometimes with those more difficult.

Remaining indifferent and distancing implies the inability to connect with or acknowledge how another is, feels or perceives.

—Shelby Lee Adams

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Copies of salt & truth are still available.

Published 2012, Candela Books, Richmond, VA.

The Center for Creative Photography at Tucson is assembling a permanent collection and archive of my work. Currently over 150 images are available to view at the link below.

CCP/SLA Archive

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Armeldia

Kelly and Armeldia, 1983

Armeldia, 1983

Armeldia, 1993

___________________________________________________________

Truth

“The Stories get past on and the truth gets passed over. As the sayin goes. Which I reckon some would take as meanin that the truth cant compete. But I don’t believe that. I think that when the lies are told and forgotten the truth will be there yet. It don’t move about from place to place and it dont change from time to time. You cant corrupt it any more than you can salt salt. You cant corrupt it because that’s what it is. It’s the thing you’re talking about. I’ve heard it compared to the rock-maybe in the bible-and I wouldn’t disagree with that. But it’ll be here even when the rock is gone.”

“You were doin something for folks that couldnt do it for theirselves.”

“I think the truth is always simple. It has pretty much got to be. It needs to be simple enough for a child to understand. Otherwise it’d be too late. By the time you figured it out it would be too late.”

Cormac McCarthy

No Country For Old Men*

________________________________________

Tammy

Tammy, 1977

Tammy with Shucky Beans, 1983

Roxanne Doorway, 1983

[Tammy in doorway]

Tammy, 1987

Tammy, 1996

Tammy, 2003

Describing the home in which Tammy was born, her brothers said, "It was a two-room wood plank shotgun house with a door at each end and three windows, was all it had. The walls were covered with roofing paper, cardboard was nailed up over that, and then wallpaper was put on to cover that and to look nice. Before Tammy was born there were five of us children living with Mommy in that house. The house only had one stone fireplace in the middle. Our mother used that to keep us warm and cook with. She used an old metal grill, like out of an old refrigerator, to put pots and pans on to cook with in the fire place. We used wood and coal for fuel. Six months before Tammy was born our mother had just got our first electric cooking stove."

Original story published in 1998 in Appalachian Legacy, by The University Press of Mississippi, author Shelby Lee Adams.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Troy [age 95] 2003

Shelby and Troy, 2003

"I stilled my own whiskey, raised my own bread and meat, growed the tobacco I chew, done a mite of everything, and not to much of anything."

—James Still

Pattern of a Man and Other Stories*

Claude with Rooster, 2005Mud Lick

Ronnie Holding Jeremy, 08

Unpublished

William and Breanna, 2003

unpublished

Girl at Kingdom Come Creek, 1987

Estill, 1990, 4x5 Polaroid above.

All photo sessions began by sharing and giving my subjects Polaroids, from 1974 - 2010 this was my procedure. By 2010 4x5 Polaroid film was no longer available, then I began working with a digital camera so I could still show and share images visually with my subjects as we made photographs. Except with a few new subjects my manner of working was well established.

The Granite Man, 1979

From series: Stenger's Cafe

In the mountains when someone opens their door to you, they open their hearts to you forever. This is part of the drawing power of the mountains and its people, that makes this process an Eternal Returning. This drawing power perhaps not accessible to all.

—Shelby Lee Adams

Johnny, 1988

Hall's Family Porch, 98

Boys at Hog Pen, 1981

Roxana

Grandpa's Chair, 1971

Vicco, 1997

Arnold's Living Room Wall, 2002

______________________________

Below not a mountain writer but an important message by

Robert F. Kennedy.